In response to the earlier post on the languages of India, several readers have asked about the scripts used in India, early and modern. I have combined my answer to their various questions into this single post.

Q: When did writing first appear in India? What were the earliest scripts used? What scripts are used in India today? Are they the same or related to the early scripts?

THE INDUS SCRIPT

The earliest evidence of writing in India comes from the Indus Valley civilisation, which dates back to about 3000-1800 BCE. The Indus or Harappan script is a pictographic script and several thousand specimens of it survive on steatite seals, clay sealings, terracotta and faience amulets, copper plates, and bronze implements.

However, even a hundred years after its discovery, the Indus script remains undeciphered. It is an unknown writing system and the inscriptions discovered are very short, consisting of no more than five signs on the average. Nor do we know, or have any means of knowing, the language spoken by the Indus people. Unless there is a breakthrough discovery of the Rosetta Stone kind, the Indus script is likely to remain undeciphered. This script died out with the Indus civilisation.

Writing next appears in India some fifteen hundred years later, in the 3rd century BCE, with the rock and pillar inscriptions of the Mauryan emperor, Ashoka. It is difficult to believe that the complex cultures that composed the Vedas and the Upanishads, or gave rise to Jainism and Buddhism, did not have any form of writing at all. But we have no definitive evidence to the contrary, textual or archaeological. (Salomon, 1982).

ASHOKA’S ROCK AND PILLAR INSCRIPTIONS

Ashoka (c. 274-232 BCE) ruled over a vast empire that stretched from Iran in the west to the Brahmaputra river in the east, and from the mountains of the Hindu Kush and Himalayas in the north to almost the southern edge of the Deccan plateau in peninsular India. He laid down rules of social and moral behaviour for his people and set down his edicts as inscriptions on rock surfaces and polished sandstone pillars which he located all across his extensive empire.

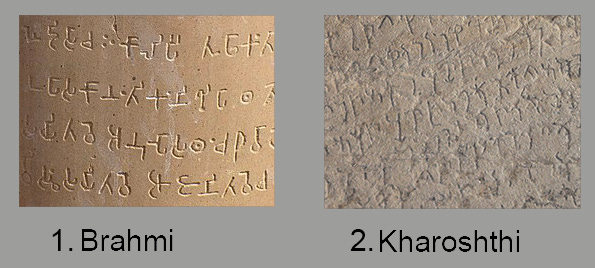

Most of Ashoka’s inscriptions were written in the Brahmi script; some, in the north-west regions of his empire were in the Kharosthi script (and some, discovered later, were in Greek and Aramaic).

BRAHMI AND KHAROSTHI

There has been much controversy over the origin of these scripts, and the date when they were first used.

Origin and date of first use

Brahmi appears suddenly, almost fully-developed, in the inscriptions of Ashoka (Salomon, 1982). In 1895, the German scholar Georg Buhler proposed that the Brahmi script was derived from the Phoenician and went as far back as the 8th century BCE. Indian scholars suggested that the Brahmi and Kharosthi scripts were derived, directly or indirectly, from the Indus; however, there is no convincing evidence to support this theory. They, too, proposed a much older date for writing in India than the Ashokan inscriptions, basing their conclusions on alleged evidence in texts such as the Buddhist Pali canon and the 6th century BCE Ashtadhyayi, the treatise on Sanskrit grammar by Panini. A few minor inscriptions in Brahmi have been found that might possibly be pre-Ashokan or even pre-Mauryan, but they have not been conclusively dated. The edicts of Ashoka from the third century BCE remain the oldest, securely datable examples of writing in these scripts. (Salomon, 1995).

More recent studies assign the origin of Brahmi and Kharosthi to the early Mauryan era (ie, the late fourth to mid-third centuries BCE) and suggest their derivation from Semitic or Semitic-derived scripts.

In 1979, the historian S.R. Goyal in his essay “Brahmi: an invention of the Early Mauryan Period”, argued that “in all probability brahmi was invented in the age of Ashoka”, that the Indians of the Vedic and early Buddhist periods were illiterate, and that “the idea…of writing came from the West.” Goyal based his conclusions on many factors including the complete absence of any reliably datable specimen of pre-Ashokan writing, accounts by Greek writers such as Megasthenes testifying to the absence of writing in the early Mauryan period, the evident influence of Indian phonetic and grammatical theory on the structure of the early scripts, and the primitive and uniform appearance of Ashokan Brahmi (Salomon, 1995).

Indologist Harry Falk has gone as far as to suggest that Brahmi may have been created under Ashoka himself. Salomon suggests that Kharosthi is most likely older, having probably been developed in the northwestern India during the fourth, or even the fifth, century BCE (Salomon, 1996).

The debate on the origin of these scripts and the date of their first use continues. Nevertheless, it is with the appearance of the Brahmi and Kharosthi scripts that the story of writing in India truly begins.

BRAHMI: the source of all the indigenous scripts of India

From its first attested appearance, Brahmi was used all over the Indian subcontinent, except in the north-west, where Kharosthi was the script of choice. Initially, Brahmi was unitary all over the subcontinent, but over the centuries, regional variations appeared, to gradually become separate scripts. The earliest, distinct regional variants are those of South India, including the Brahmi used for old Tamil inscriptions (Salomon, 1996). By about the third century CE, there were several distinct regional variants, and by 1000 CE, these had differentiated to the point that they were “independent scripts” whose common origin was not “apparent to the casual observer” (Salomon, 1996). In time, these regional scripts became associated with regional languages.

Brahmi is the ultimate source of all the indigenous scripts of India. It also spread to other parts of Asia during the first millennium CE, and is the source of the major Southeast Asian scripts such as Burmese, Thai, Lao, and Khmer, of the Tibetan script, and several Central Asian scripts not in use. It thus rivals Aramaic and Arabic “in the number and range of its varieties and derivatives” (Salomon, 1996).

KHAROSTHI: a regional script

Kharosthi, on the other hand, was very much a regional script that died out in ancient times. In the Indian subcontinent, it was restricted to the northwest, in regions corresponding to northern Pakistan and eastern Afghanistan. It fell out of use by the third century CE, when it was replaced by derivatives of Brahmi. Meanwhile, Kharosthi (with Brahmi) spread to Central and Inner Asia. Several examples of its use dating to the second and third centuries CE have been found in parts of China and Uzbekistan. Documents believed to be in a local derivative of Kharosthi and dated to as late as the seventh century CE have been found in several places along the old Silk Route in Inner Asia. But except for these Kharosthi, unlike Brahmi, did not undergo any major variations and left no modern descendants (Salomon, 1996).

Script type

The Brahmi script is written from left to right, and, especially in its earlier forms, has an angular, symmetrical, and definitely monumental appearance, while the Kharosthi script is written from right to left and is more cursive (Scharfe, 2002). Despite superficial differences, Brahmi and Kharosthi are systemically of the same type, ie, they are both diacritically modified consonant syllabic scripts, or alphasyllabaries. In such scripts, each consonant–vowel sequence is written as a unit with each unit based on a consonant letter and the vowel notation secondary. All Indic and other scripts derived from Brahmi follow the same system. This “characteristically Indian script type” (Salomon, 1996) is particularly suited to the sounds and structure of Indian languages.

MODERN INDIAN SCRIPTS

There are three main kinds of scripts used in India today: derivatives of the Brahmi script, derivatives of the Arabic script, and Roman.

Among the many descendants of Brahmi are Devanagari (used for Sanskrit, Hindi, Marathi, and other Indian languages), the Bengali and Gujarati scripts, and those of the Dravidian languages (which include the four major South Indian languages, Tamil, Telegu, Malayalam and Kannada).

Over time various Muslim communities in India adopted the Arabic or Perso-Arabic script for their own languages. These languages include Urdu and Kashmiri. In southern India these languages include Konkani, Malayalam and Tamil, whose forms written with the Arabic script are known as Nawayathi, Arabi-Malayalam, and Arwi (Saldanha). In the north, Punjabi-speaking Muslims use the adapted Arabic script Shahmukhi to write Punjabi, whilst Punjabi-speaking Sikhs and Hindus use Gurmukhi.

In the case of some languages, whole new scripts have been invented. An example of this is the Ol Chiki script, invented in 1925 by Pandit Raghunath Murmu, for Santali.

The Roman script is used for English. It is also being increasingly used for other languages on chat, email, SMS and social media. Some academics have put forward a case for writing *all* Indian languages in the Roman script.

Do you know of other, unusual or interesting scripts? Do write in via the comments!

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY AND FURTHER READING

Kurzon, Dennis. “Romanisation of Bengali and Other Indian Scripts.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 20, no. 1 (2010): 61–74. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27756124.

Parpola, Asko. “Deciphering the Indus Script.” Harappa.com. Accessed December 28, 2022. https://www.harappa.com/script/parpola0.html.

Murmu, Punam. “The Making of Santali Ol Chiki Script: In Conversation with Ram Chandra Baskey.” Adivasi Lives Matter, December 22, 2021. https://www.adivasilivesmatter.com/post/the-making-of-santali-ol-chiki-script-in-conversation-with-ram-chandra-baskey.

Saldanha, Ayesha. “The Arabic script in South India.” Mashallah News. Accessed December 27, 2022. https://mashallahnews.com/language/arabic-script-india.html.

Salomon, Richard. Journal of the American Oriental Society 102, no. 3 (1982): 553–55. https://doi.org/10.2307/602326.

Salomon, Richard. Review of On the Origin of the Early Indian Scripts, by Oskar von Hinüber and Harry Falk. Journal of the American Oriental Society 115, no. 2 (1995): 271–79. https://doi.org/10.2307/604670.

Salomon, Richard G. “Brahmi and Kharoshthi,” The World's Writing Systems, Peter T. Daniels and William Bright (Oxford Univ Press, 1996).

Scharfe, Hartmut. “Kharoṣṭī and Brāhmī.” Journal of the American Oriental Society 122, no. 2 (2002): 391–93. https://doi.org/10.2307/3087634.

Language Atlas of India, 2011. New Delhi: Registrar General and Census Commissioner, India ; Ministry of Home Affairs, 2011.

“OL Chiki Script.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ol_Chiki_script.

Fascinating read about the history of Indian languages and the fusions of different cultures that have influenced the development of its scripts...well researched!

Thanks for your meticulous and enriching research and clarity of writing. Really love Eaten by a Fish and the hard work,effort and skill that goes into producing your lovely newsletter with such regularity. Reading about the Santhali script being recently developed reminded me of the Gondi script in Maharashtra. The Gonds have rich oral traditions but their script was usually dependent on the regions they lived in till recently( Devnagri/ Tamil or Telegu for example). Here is a link for further information: https://omniglot.com/writing/masaramgondi.htm