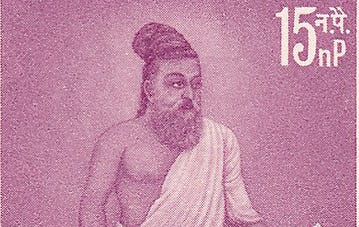

Valluvan’s Wisdom and His Immortal Couplets

An introduction to Valluvan and his Thirukural

Tamil scholars and students alike consider Kamban, Valluvan and Ilango the three greatest writers of Tamil literature. Kamban was honoured by the Chola king with the title of Kavi Chakravarthy, ‘the emperor of poets’. His literary works include the Tamil version of the Ramayana. Valluvan was a great poet and philosopher. His most famous work is the Thir…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Eaten by a Fish to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.