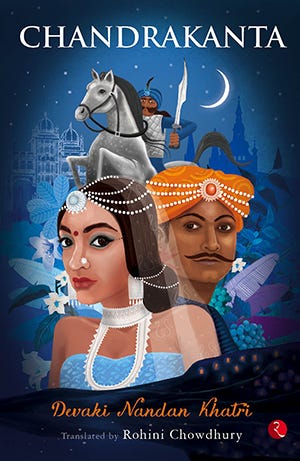

We begin our exploration of popular Indian fiction with Chandrakanta, a wonder tale of magic, mystery and adventure, that became modern India’s first bestseller.

CHANDRAKANTA

BY DEVAKI NANDAN KHATRI

Translated by Rohini Chowdhury

(Published: Rupa Publications, 2015)

Part 1, Narrative 1

It is evening. In the waning light, on a lonely plain beneath a hill, can be seen two men; perched upon a rocky outcrop, they are deep in a conversation. The men are Birendra Singh and Tej Singh.

Birendra Singh, who appears to be some twenty-one or twenty-two years of age, is the only son of Raja Surendra Singh, the king of Naugarh. The other, Tej Singh, is Prince Birendra Singh’s closest friend, and the beloved son of Jeet Singh, Raja Surendra Singh’s divan. Tej Singh is quick and alert, and keeps a sharp lookout even while immersed in conversation with the prince; at his waist hangs a dagger, under his arm is slung a small bag, and in his hand he carries a coil of rope. Before them stands a horse, securely tethered to a sturdy tree.

Prince Birendra Singh is speaking.

“Tej Singh,” said the prince, “see what an evil affliction Love is, to have brought me to this state! You have, often enough, brought me Princess Chandrakanta’s letters from Vijaygarh and carried mine to her, and you know that this exchange of letters clearly shows that Chandrakanta loves me as much as I love her. And even though our kingdom is only five kos distant from hers, we have not been able to come together. Look, even in this letter Chandrakanta beseeches me to meet her soon.”

“I can take you to her easily enough,” replied Tej Singh, “except that these days Chandrakanta’s father, Maharaj Jai Singh, has set a strict guard around the palace. What’s more, his Minister’s son, Kroor Singh the Cruel, has become enamoured of the princess. He is fully aware of your feelings for her, and has instructed his two aiyaars, his spy-magicians, Najim Ali and Ahmed Khan, to keep a close watch on the palace all the time. Though Chandrakanta hates him, and he knows the king will never give his daughter in marriage to a mere minister’s son, Kroor Singh lives on hope and dislikes intensely your attachment to the princess. He has also, through his father, informed the king of your love for Chandrakanta, and it is on account of this that the guard on the palace has been increased. I am not comfortable taking you there right now, not till I have caught those mischief-makers and taken them prisoner.”

“Let me go to Vijaygarh once more,” continued Tej Singh, “and meet Chandrakanta and her friend, Chapala, again. Chapala loves Chandrakanta more than her life. She is also an aiyaara, and except for her, there is no one in Vijaygarh I can depend on to help me. Once I have discovered what our enemies are plotting and seen how far their cunning has taken them, I will return and only then will I give an opinion on whether you should go there or not. We should not do anything in a hurry and without understanding the situation fully. Otherwise, we may end up getting trapped or taken prisoner.”

“Do what you think is possible. I rely only on my strength, but you have both your strength and the skills and cunning of your aiyaari,” replied Birendra Singh.

“I have also learnt that Kroor Singh’s two aiyaars, Najim and Ahmed, came here recently and paid a visit to our king. I wonder with what cunning scheme in mind they had come…” mused Tej Singh. “It’s a pity I wasn’t here at the time.”

“Here you are trying to trap the two aiyaars of Kroor Singh, while they are scheming to capture you! May God look after you! Anyway, go now, and somehow make it possible for me to meet Chandrakanta,” said Birendra Singh.

Tej Singh stood up at once, and leaving Birendra Singh there, left on foot for Vijaygarh. Birendra Singh untied the horse from the tree, and mounting it, left for his fort.

Thus begins Chandrakanta, Babu Devaki Nandan Khatri’s extraordinary first novel. Khatri began writing Chandrakanta in 1887. He was all of twenty-six years old at the time, and this was his first foray into fiction. As he explains in the preface to the first edition, “I have never written a book before, this is my first attempt, so if there be errors and mistakes, it is not a matter for surprise…”. The first part of his novel was published in 1888 in Banaras, by his friend, Babu Amir Singh, owner of the Hariprakash Yantralay. Khatri wrote his novel in four parts, his fans welcoming each new part with unabated eagerness and enthusiasm. At almost 300 pages, and with a total of 93 chapters across the four parts, Chandrakanta became the longest Hindi novel of the nineteenth century. All four parts were published separately in 1891, and then together in one volume, in 1892.

Chandrakanta was so successful that by 1894, Khatri was able to set up his own press, the Lahari Press, and start his own monthly fiction magazine, ‘Upanyas Lahari’. He also began publishing Chandrakanta Santati (‘Chandrakanta’s Descendants’), the sequel to Chandrakanta; he wrote the sequel in twenty-four parts, completing the final part in 1905. Khatri also published Urdu editions of Chandrakanta, and at least one edition in Nepali (Gorkhabhasha)1. Khatri continued to publish Chandrakanta and Chandrakanta Santati in various editions, Hindi and Urdu, to suit every pocket, under his own imprint of the Lahari Press, though printed by other presses. As Chandrakanta and its sequels continued to grab the popular imagination, readers would mob the premises of the Lahari Press whenever a new part of the novel was expected.

Khatri capitalized on his success by continuing the story in a second sequel, Bhutnath; this was based on a character from Chandrakanta Santati. He wrote and published six parts of this sequel between 1907 and his death in 1913. After his death, his son Durga Prasad Khatri took over the management of the Lahari Press; he also continued and completed Bhutnath, writing another fifteen parts of the story between 1915 and 1935. The novels continued to sell so well that Durga Prasad Khatri further continued the story in a third, six-part, sequel called Rohtasmath.

Though never accepted as ‘literature’ by the Hindi literary establishment due to the levity of its subject matter, the very popularity of Chandrakanta makes it a landmark event in the history of Hindi literature, and particularly so, in the history of the Hindi novel. From the point of view of commercial Hindi publishing, which was still in the early stages of development at the time, Chandrakanta (and its sequels) managed to create in readers the habit of reading novels in Hindi2, introducing them to the conventions of the modern novel, a habit that later, more ‘literary’ writers in Hindi were able to exploit. Chandrakanta’s success also gave birth to a whole new sub-genre of Hindi fiction — that of the tilismi and jasusi detective novels (to which Khatri himself contributed several works), which became hugely popular as well.

Khatri drew heavily on the Persian-Arabic tradition of the dastan and qissa for his novel.

‘Dastan’ and ‘qissa’ both mean ‘story’ in Persian, and belong to a narrative genre that may be traced to medieval Iran. There is little difference between the two, except perhaps of length (dastans are longer) and the terms are often used interchangeably. The dastan was oral in nature, and usually recited by a dastan-go or professional storyteller. In India, dastans acquired even greater popularity under the Mughal emperor, Akbar. One of the most popular of the dastans of the time was the Dastan-e-Amir Hamzah, relating the life and adventures of Amir Hamzah, the Prophet’s uncle. Akbar not only memorized large sections of this dastan, but also commissioned an illustrated version of it which, known as the Hamzahnama, is regarded as one of the crowning achievements of Mughal art. Despite their popularity under the Mughals, dastans really came into their own in India in the nineteenth century, when they began to be composed in Urdu. By the middle of the nineteenth century, a few dastans had also appeared in print, including Ghalib Lakhnawi’s hugely popular Urdu version of Amir Hamzah.

Like Amir Hamzah and other Urdu dastans of the time, Khatri’s novel is set in the courtly world of princes and princesses, magnificent palaces and gracious gardens, where love and beauty rule the day and chivalry and honour are valued above life itself, where the beautiful Princess Chandrakanta, imprisoned in an ancient tilism or enchantment, must wait for rescue, while her lover, the valiant Prince Birendra Singh, must battle jealous rivals and break the ancient enchantment in order to reach her. Yet, as in the dastans, the real protagonists of the story are not the prince and the princess, but their secret agents, the ‘spy-magicians’ known as aiyaars. Both the prince and the princess have their own cohort of aiyaars and aiyaaras, and, as in most dastans, it is really the aiyaars who determine the direction and set the pace of the story. Thus, Khatri’s tale has all the elements of a traditional dastan: descriptions of war, and battles that help the prince to prove his valour; elaborate enumerations of royal splendour and details of courtly gatherings; beauty as embodied in women and love; ancient enchantments, and clever and ingenious aiyaars with their inventive, and sometimes cunning, tricks and plans (aiyaari). A virtuoso dastan-go would often ‘stop’ the dastan in order to offer his listeners long lists and detailed descriptions of ‘dastan-mandatory’ items. Khatri, too, offers his readers detailed descriptions of nature, feminine beauty, and battles and often gives lists of plants and trees, royal treasure and other items, but unlike the traditional dastan-go, he keeps his descriptions short, never allowing his narrative to pause or flag.

Khatri was also was influenced by the writings of the Bengali poet and novelist, Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, and the English novelist W.J. Reynolds. In Chandrakanta, Khatri brings together all the narrative elements of a dastan; at the same time, he successfully makes the leap from the traditional, oral forms of storytelling to the modern conventions of the novel, so that even those critics who refuse to accept Chandrakanta as a work of literary merit, accept Khatri’s role in introducing readers to the new literary form of the novel.3

Chandrakanta and its sequels together rival the length of the Dastan-e Amir Hamzah (one version of which is reputed to have taken took up 46 volumes, each a thousand pages long!). Yet Devaki Nandan Khatri claimed that he wrote his tale ‘in brief’; in my opinion, by this he was referring not to the length of Chandrakanta and it sequels, but the manner in which he wrote them. Khatri did not write Chandrakanta in one sitting or even in one location — he wrote it in bits and pieces, wherever it was he found himself when the urge to write came upon him. He kept no notes, never needed to refer back to what he had written before, or to ever re-read or correct his first draft. He wrote Chandrakanta and its sequels over a twenty-year period, from 1887 to 1913, and not once did he need his memory to be refreshed, which made his memory even more stupendous than his imagination!

DEVAKI NANDAN KHATRI (1861 - 1913)

Babu Devaki Nandan Khatri was born in 1861 in Pusa, in the home of his maternal grandfather, Babu Jivanlal Mahato. His mother was Babu Jivanlal’s only daughter. His father, Lala Ishvardas, came from an old and illustrious family of Punjab; unrest in Lahore during the reign of Maharaja Sher Singh had caused him to leave that city in the 1840s for Kashi (Banaras), where he had settled. In accordance with Babu Jivanlal’s wishes that his son-in-law come to live in Pusa with him, Lala Ishvardas had moved to Pusa after his wedding, and lived there for several years. Babu Jivanlal, a wealthy landowner, enjoyed the status and lifestyle of a minor raja, so that the young Devaki Nandan spent his childhood in royal courts and palaces, watching and learning the ways of kings and princes up close, a familiarity that peeps through in Chandrakanta.

Meanwhile, Lala Ishvardas, unable to get along with his father-in-law, moved back to Kashi, where he set up a successful business supplying gold and gold ornaments to various royal courts. When he was old enough, Devaki Nandan joined his father in Banaras, becoming actively involved in his father’s business. Lala Ishvardas conducted business with several small kingdoms, including the tiny kingdom of Tekari in Gaya, where he had a large warehouse and office. Devaki Nandan learnt the business quickly, so that very soon he was given sole charge of the Gaya office, dealing directly with the Raja of Tekari. Here he enjoyed an independent lifestyle, with a good income and plenty of money at his command. His was a colourful personality, and the story goes that on one occasion he spent Rs 5000, a minor fortune in those days, on flying kites! Soon, though, his youth and impetuosity landed him in trouble, and incurring the displeasure of the Raja of Tekari, he returned home to his father in Kashi.

His father, greatly displeased, forbade him to leave the city. Raja Ishvariprasad Narayan Singh was king of Kashi in those days. As it happened, the Raja’s sister was married to the ruler of Tekari, and through his association with Tekari, Devaki Nandan’s father had become a close associate of the Raja of Kashi. Hearing of Devaki Nandan’s troubles, the Raja offered him a place in his court at Kashi. But Devaki Nandan did not want the life of a courtier, which would have bound him to the city and the court. He therefore asked that he be given the contract to farm the surrounding forests. The Raja agreed, and he was awarded the contract for the forests of Naugarh and Chakia. Devaki Nandan embraced his new occupation with great enthusiasm, roaming the forests with a merry band of friends. Unfortunately for him, one of his friends shot and killed a tiger, a sport strictly banned by the Raja of Kashi. As a consequence of this irresponsible act on the part of his friend, Devaki Nandan lost his contract and was sent home by the Raja in disgrace. His father, Lala Ishvardas, was furious, and berated him for being a good-for-nothing who messed up every opportunity that came his way. Devaki Nandan, upset and despairing, decided to attend the Rath Yatra that year; clinging to the giant wheels of the chariot he wept and asked the god Jagannath for guidance. He returned home and sitting down at his desk, pulled out a sheet of paper and scrawled a single word across the top — ‘Chandrakanta’. He wrote furiously through the night, and next morning showed his writing to his friend, Badrinath. “A young man gave me this,” he said. “What do you think? Should he keep writing?” he asked his friend. Badrinath read the chapters through, and recognized Devaki Nandan’s stamp and style. “Of course your friend should keep writing,” he replied, and declared that he had recognized this as Devaki Nandan’s own work. Thus encouraged, Devaki Nandan continued writing Chandrakanta — and the rest, as they say, is history.

Chandrakanta continues to enjoy great popularity even today.

It is worth noting that the novel has remained in print continuously for a hundred and thirty-four years, that is, since it first appeared in 1888. The family copyright on Chandrakanta expired in 1964, when the novel came into the public domain. Since then, it has been brought out by several leading Hindi publishers; Lahari Press, now headed by Babu Devaki Nandan’s grandson, Shri Vivek Khatri, continues to print and sell some 2,500 copies a year as well. The family tradition of writing sequels to Chandrakanta is being continued by Vivek Khatri, who has added more novels to the saga, including Heeron ki Ghati (‘The Valley of Diamonds’) and Shersingh.

Television

Several television shows have been inspired by Khatri’s novel. Though they have taken considerable liberties with the original, they have attracted a large viewership in India.

Translations

Chandrakanta had been translated more than once into English: In 2004, by Manju Gupta as In the Mysterious Ruins, and in 2008, for children, by Deepa Agarwal.

The enduring charm of the novel, as well as its landmark place in Hindi literature, made me venture another translation. Devaki Nandan Khatri’s language, the spoken Hindi of his times, fast-paced, simple and very effective, was both a delight and a challenge to translate.

My translation was published by Rupa Publications in 2015. The excerpts above have been published here with their permission.

What else would you like to read about in our translation section? Tell us what you think!

Francesca Orsini, Print and Pleasure: Popular Literature and Entertaining Fictions in Colonial North India, Chapter 6, p 199-200.

Francesca Orsini, Print and Pleasure: Popular Literature and Entertaining Fictions in Colonial North India, Chapter 6, p.200.

Francesca Orsini, Print and Pleasure: Popular Literature and Entertaining Fictions in Colonial North India, Chapter 6.

Very interesting, now looking forward to reading your translation of the first bestseller, Rohini!

Yes, this is truly fascinating!