An Ocean of Stories

A look at Somadeva's 'Kathasaritsagara' and other related texts

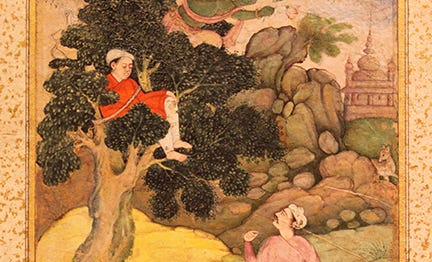

India is often said to be the ‘cradle’ of all stories, the land from which stories spread far and wide across the world. The 11th-century collection of stories known as the the Kathasaritsagara certainly adds credence to that claim. The title, translated in full, means ‘the ocean of the rivers of story’, a name that immediately brings to mind the image…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Eaten by a Fish to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.